Batching operations in Go.

Mat Ryer

·

13 Feb 2020

Mat Ryer

·

13 Feb 2020

Mat Ryer

·

13 Feb 2020

Mat Ryer

·

13 Feb 2020

Mat Ryer

·

13 Feb 2020

Mat Ryer

·

13 Feb 2020

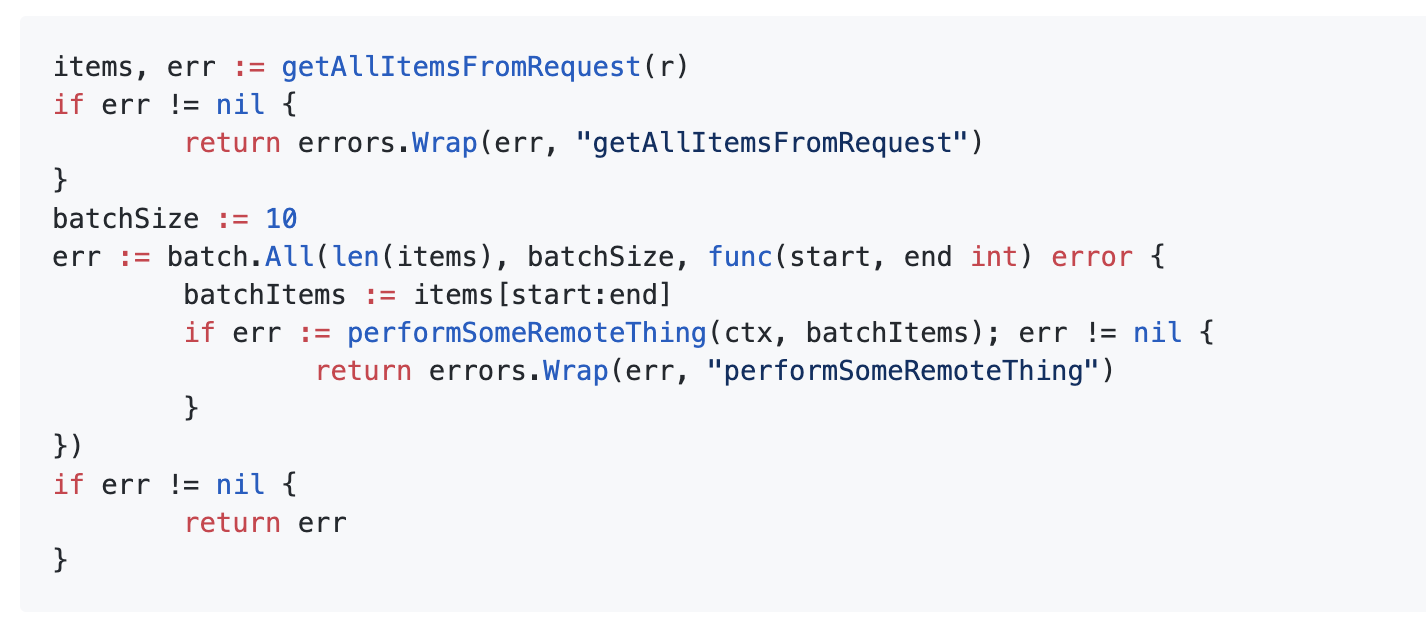

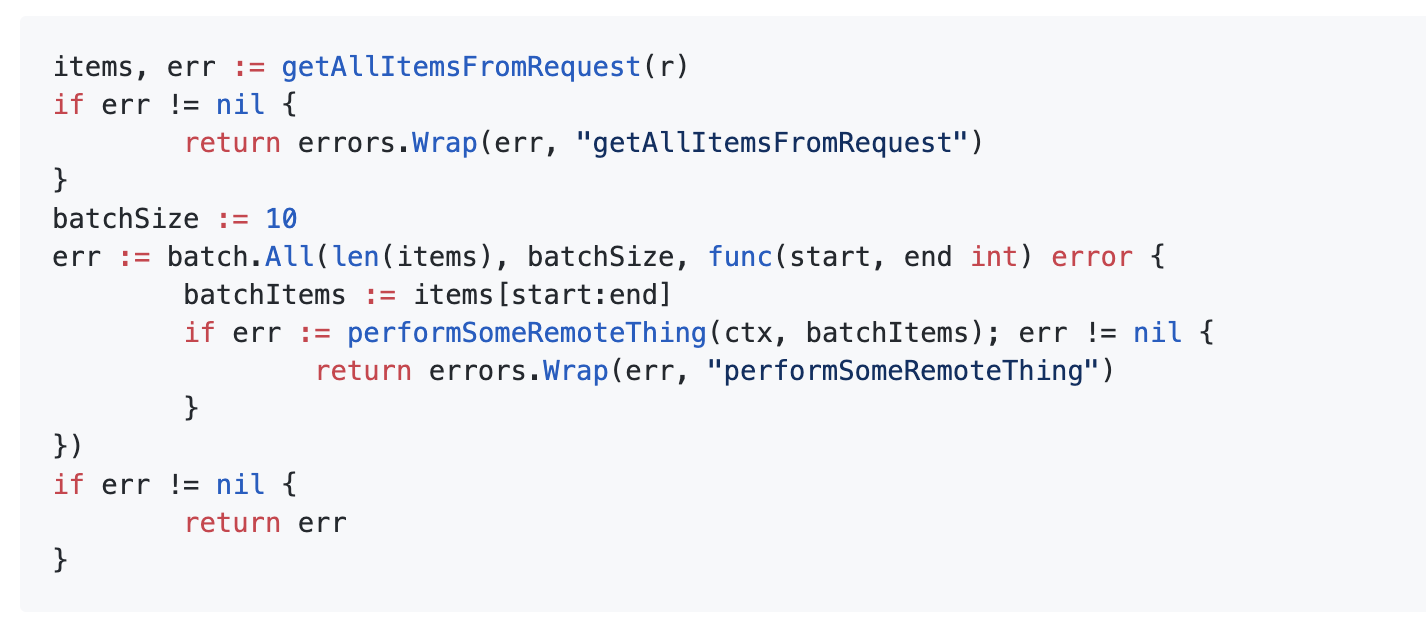

Say we have a remote call to make, and we want to break a list of items into smaller chunks to send them in batches.

It’s a fairly simple problem to solve, but we’ll look at how a well designed helper can make all the difference to the readability and stability of our code.

We always like to think of the situation the user is in when we are designing any kind of API, and this applies to functions too.

Say we have a slice of items that we want to process:

items, err := getAllItemsFromRequest(r)

if err != nil {

return errors.Wrap(err, "getAllItemsFromRequest")

}

It’s possible that the array contains thousands of items. But say we only want to process them in batches of ten, it would be nice to be able to call a method like this:

batchSize := 10

err := batch(len(items), batchSize, func(start, end int) error {

batchItems := items[start:end]

if err := performSomeRemoteThing(ctx, batchItems); err != nil {

return errors.Wrap(err, "performSomeRemoteThing")

}

})

if err != nil {

return err

}

The batch function takes the total number of items, the batch (page) size, and a function that gets called for each batch, with start and end marking the range, allowing us to re-slice the items:

batchItems := items[start:end]

In this example, if we got 105 items, the performSomeRemoteThing function would get called eleven times, each time with a different page of 10 items (the batchSize) except the last time, when it would be a slice of the remaining five items.

When solving problems like this, I find TDD to be an excellent guide and check of what I’m doing. It is especially good at confirming we don’t have any off-by-one errors, or hit any snags at the edges.

Consider the following test code:

func Test(t *testing.T) {

is := is.New(t)

type r struct {

start, end int

}

var ranges []r

err := batch(100, 10, func(start, end int) error {

ranges = append(ranges, r{

start: start,

end: end,

})

return nil

})

is.NoErr(err)

is.Equal(len(ranges), 10)

is.Equal(ranges[0].start, 0)

is.Equal(ranges[0].end, 9)

is.Equal(ranges[1].start, 10)

is.Equal(ranges[1].end, 19)

is.Equal(ranges[2].start, 20)

is.Equal(ranges[2].end, 29)

is.Equal(ranges[3].start, 30)

is.Equal(ranges[3].end, 39)

is.Equal(ranges[4].start, 40)

is.Equal(ranges[4].end, 49)

is.Equal(ranges[5].start, 50)

is.Equal(ranges[5].end, 59)

is.Equal(ranges[6].start, 60)

is.Equal(ranges[6].end, 69)

is.Equal(ranges[7].start, 70)

is.Equal(ranges[7].end, 79)

is.Equal(ranges[8].start, 80)

is.Equal(ranges[8].end, 89)

is.Equal(ranges[9].start, 90)

is.Equal(ranges[9].end, 99)

}

The test uses the batch function, and appends the details of each call to a ranges slice.

After the process, we check that the err was nil, and then make assertions about all the indexes we expect.

What’s nice about how explicit this is, is that we can actually think about and check each value. We know exactly what the start and end values should be, so we can spell it out.

This is easier to reason about than the upcoming looping and counting logic we’re about to write.

batch functionOur batch function is going to keep a start index i (starting at 0 the first item) and call the eachFn(i, end) for each batch, passing in the start and end indexes. Each iteration,

i is recalculated to be the next item: end + 1.

// batch calls eachFn for all items up to count.

// Returns any error from eachFn except for Abort it returns nil.

func batch(count, batchSize int, eachFn func(start, end int) error) error {

i := 0

for i < count {

end := i + batchSize - 1

if end > count-1 {

// passed end, so set to end item

end = count - 1

}

err := eachFn(i, end)

if err == Abort {

return nil

}

if err != nil {

return err

}

i = end + 1

}

return nil

}

In the batch function above, you can see that we check for a special sentinel error (coined by Dave Cheney) called Abort:

if err == Abort {

return nil

}

If the err returned from the callback is Abort the batch function stops iterating and returns nil, indicating a happy exit.

The Abort variable can be declared like this:

// Abort is a sentinel error which indicates a batch

// operation should abort early.

var Abort = errors.New("abort")

Rather than define the callback signature func(start, end int) error inline, it’s better to declare a type.

This allows you to document the callback, and how it should be used.

// BatchFunc is called for each batch.

// Any error will cancel the batching operation but returning Abort

// indicates it was deliberate, and not an error case.

type BatchFunc func(start, end int) error

The comment should say everything about the behaviour of this callback.

We recommend you just copy the code for this function (and its test) to your own project (even if you end up having a couple of copies of it, what’s the harm in that?).

This package is maintained as a Go module over at https://github.com/pacedotdev/batch.

The mechanics are fairly simple, but the code is encapsulated and well tested.

A lot of our blog posts come out of the technical work behind a project we're working on called Pace.

We were frustrated by communication and project management tools that interrupt your flow and overly complicated workflows turn simple tasks, hard. So we decided to build Pace.

Pace is a new minimalist project management tool for tech teams. We promote asynchronous communication by default, while allowing for those times when you really need to chat.

We shift the way work is assigned by allowing only self-assignment, creating a more empowered team and protecting the attention and focus of devs.

We're currently live and would love you to try it and share your opinions on what project management tools should and shouldn't do.

What next? Start your 14 day free trial to see if Pace is right for your team

Mat Ryer

Mat Ryer

or you can share the URL directly:

https://pace.dev/blog/2020/02/13/batching-operations-in-go-by-mat-ryer.htmlThank you, we don't do ads so we rely on you to spread the word.

If you have any questions about our tech stack, working practices, or how project management will work in Pace, tweet us any time. :)

— pace.dev (@pacedotdev) February 25, 2020

How I write HTTP services after eight years #Golang #HTTP #WebServices

Context-aware io.Reader for Go #Tech #Golang

How code generation wrote our API and CLI #codegen #api #cli #golang #javascript #typescript